Are You Playing By the Rules? ...I Think Not!

Most people will read the rules once before the first game, and then never again.

During our development of Zombie Teenz Evolution, we ran 2 successive playtesting sessions: the first with 5 families, and the second with 4 families. Here is what we learned.

Most people will invent a rule rather than look it up.

It turns out that the majority of people will not refer to the rulebook when they're not sure about a game's rules, and would rather make a guess, or invent a rule instead of looking it up.

Most people will read the rules once before the first game, and then never again.

We watched players incorrectly interpret one particular rule during the Zombie Teenz tests, resulting in super-powerful zombies that made the game nearly impossible to win. Despite their extensive gaming experience, these families didn't have the reflex to go check the rule, even though their instincts told them that something was probably wrong.

Another family misread the effect of one of the TEENZ's powers, making it completely overpowered, and significantly stronger than all the other powers. This meant that it was practically impossible to lose. The father said, "Wow, that's really powerful!" ...without looking to see whether it might be a bit too good to be true.

The moral of the story? We must WRITE rules in a way that they will be understood and internalised after the first read-through. This seems obvious, and yet... In the face of the amount of work that constitutes publishing a board game, the attention to detail required for writing rules and having them read, re-read, and re-formulated makes it sometimes all to easy to check the 'Done' box too quickly. After all, the rules are written, complete, and comprehensible... All the points have been covered! We can move on to other, more pressing matters, right? No?

Nope. When writing rules, we have to put ourselves into the brain of the person who knows nothing about our game. We have to make as much use as possible of elements of logic that will be familiar to them. We have to predict all of their reactions and possible interpretations, even if they are wrong! We have to have the following dialogue with ourselves: "If I write this, there's a chance that someone reading this too quickly will think... [insert incorrect interpretation here]. So how can I 'trap' the reader to force them to understand the right thing?"

Nope. When writing rules, we have to put ourselves into the brain of the person who knows nothing about our game. We have to make as much use as possible of elements of logic that will be familiar to them. We have to predict all of their reactions and possible interpretations, even if they are wrong! We have to have the following dialogue with ourselves: "If I write this, there's a chance that someone reading this too quickly will think... [insert incorrect interpretation here]. So how can I 'trap' the reader to force them to understand the right thing?"

Where rules are written matter!

In the very rare cases where players will actually go to the rulebook to check on a rule during the game, if they don't find the pertinent information in the first place they look, they'll assume that the answer isn't in the rules at all. This means that we have to ask ourselves the question, "where should this rule be written?" And we have to ask ourselves that twice. First, so that the rule is understood during the first read-through as part of a logical structure of discovery. And secondly so that it is easily found during a rule-check while the game is running. This is why we will often reiterate certain rules in multiple places in the rulebook. A flagrant example of this is in Master Word, where the victory and defeat conditions can be found in 3 different spots: 1. At the beginning of the rules (Goal); 2. When we explain how these conditions can arise during gameplay; 3. In the End of Game section!

In the very rare cases where players will actually go to the rulebook to check on a rule during the game, if they don't find the pertinent information in the first place they look, they'll assume that the answer isn't in the rules at all. This means that we have to ask ourselves the question, "where should this rule be written?" And we have to ask ourselves that twice. First, so that the rule is understood during the first read-through as part of a logical structure of discovery. And secondly so that it is easily found during a rule-check while the game is running. This is why we will often reiterate certain rules in multiple places in the rulebook. A flagrant example of this is in Master Word, where the victory and defeat conditions can be found in 3 different spots: 1. At the beginning of the rules (Goal); 2. When we explain how these conditions can arise during gameplay; 3. In the End of Game section!

Players will add rules to the game.

Imagine a monster that acquires a special defense ability, and in order to be eliminated and returned to the supply, it must be attacked twice, rather than once. A significant proportion of players put that ability back on the monster when it came back into play, even though the rules did not specify that they should. They will argue that we didn't specify that they shouldn't add the special defense, even though it doesn't make sense to add something. We found that it's always best to be precise.

Examples have more than one function.

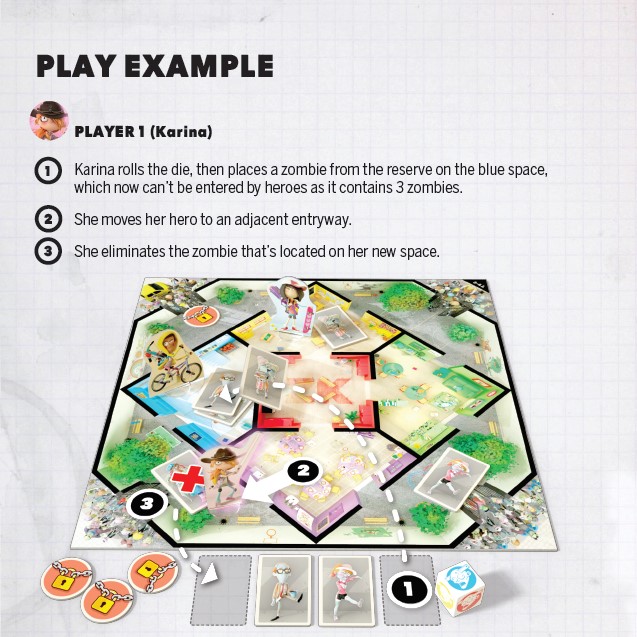

Examples are not only good for clearly illustrating rules, they are also great at underlining a rule by covering special situations that would be too complicated to explain textually. For example, you open an envelope and find boots that allow you to move two spaces (instead of just one) in a game that forbids you from being in the same space as another Hero or a Monster. The rule is clear... but then you ask yourself, "Can I move through a space with another Hero or Monster, as long as I end my movement in an empty space?" Instead of explaining this exception in the rules, it's better to simply use an example.

So in Zombie Kidz Evolution, many playtesters wondered what would happen if a die roll made a zombie appear in the same space as one of the KIDZ. If we apply exactly what is written in the rules, nothing should change. But players still asked themselves that question. They hesitated. This is why we used this situation as an example in the rules:

2 Waves are Better Than 1

Doing these 2 waves of playtests took an enormous amount of time, but I am convinced that it was worth it, because:

1. We avoided doing much more work much further down the line. Yes! Zombie Kidz has enjoyed a huge amount of success, but every week we get questions about the rules. In writing the Zombie Teenz rules better than those of Zombie Kidz, we will be saving time and work once the game is out!

2. It hugely increased the overall game experience. Questions about the rules disappeared almost completely between the first and second waves, meaning that players no longer had that unpleasant feeling that something wasn't quite right during their playthroughs... a feeling that could be compounded by not being able to easily find the rule that would erase that doubt.

Playtest Your Rules!

Playtesting games is very important; there is no other way to properly design and develop a game, but we have learned the importance of playtesting our rules too. Your game may work just fine, but if your players don't grasp that the first time round... well, there may not be a second time!

Take a peek behind the curtain...

Once a month Scorpion Masqué's Grand Poobah shares his thoughts with you. From how the market has evolved, to writing rules that make sense, with detours into game mechanisms, you will get a glimpse at the board game industry from the point of view of a publisher.

Copyright © 2026 - Le Scorpion Masqué